Ideas, entrepreneurial ventures, resounding oversights, patents and inventors-these are just some of the ingredients of the stories we are about to tell you.Today we present five machines that have revolutionized the world of printing since the nineteenth century.

Typographers, scientists and inventors have never stopped looking for improvements to Gutenberg’s fantastic invention: movable type printing. In particular, beginning in the nineteenth century, ingenious machines attempted to facilitate various activities related to printing, such as: page composition, typeface creation, and actual printing.

Linotype, rotary press, offset press, Lumitype are some of the inventions that, for the most diverse reasons, were most successful and helped define what we now call “printing.” These machines made it possible to print more, faster, more efficiently by ferrying printing from the industrial revolution and the digital revolution.

The press

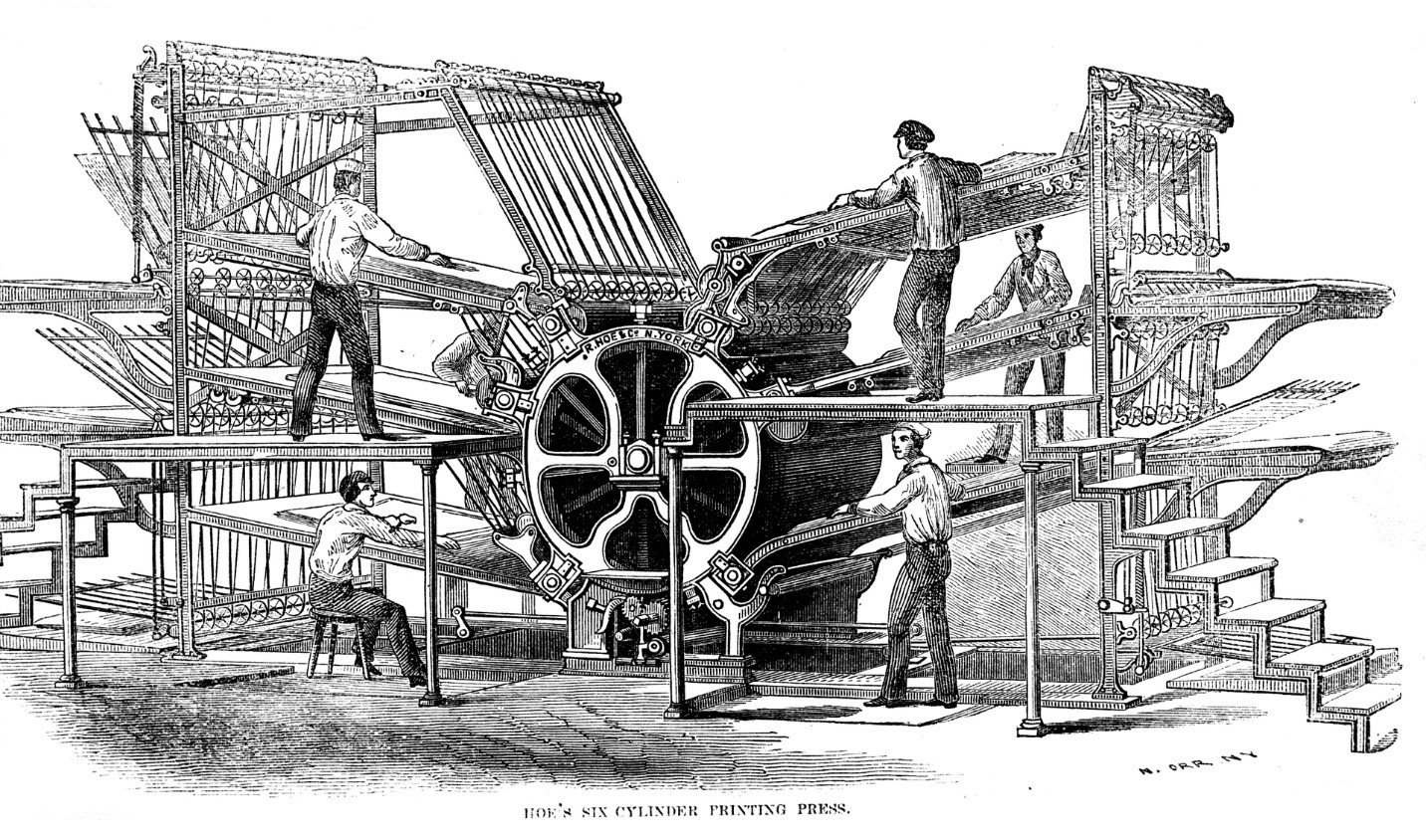

Big rollers where freshly printed newspapers run at breakneck speeds-who doesn’t have that image in their head? Presses have entered the common imagination today; however, this invention appeared relatively late in the history of printing. It was not until the nineteenth century, in fact, that people began to think about a system to replace the printing press, which had essentially remained unchanged since the days of Gutenberg.

The idea is simple: replace all the flat surfaces of the printing organs with rotating cylinders, one cylinder supporting the inked form, the other supporting the sheet. It may seem like a small invention, but switching from the flat printing press to the cylinder revolutionized the world of printing and made it much more efficient to take advantage of the discoveries of the Industrial Revolution: the steam engine and later electricity. Everything became faster, bigger, more efficient: giving way to printing as an industrial process.

It was arrived at in stages and by a sum of intuition.

In 1814, German inventor Friedrich Koenig developed the first flat-cylindrical, steam-powered press that allowed printing speed to be increased from 300 to 1100 sheets per hour. Thirty years later. American Richard March Hoe took that invention and improved on it by making the first real press. A few years later he replaced cut-sheets with reels, or large paper webs.

The first letterpress of this type was installed at the Times of London in 1870: it was capable of producing about 12,000 4-page signatures per hour. Today, some presses run sheets at about 30 mph and print more than 60,000 copies per hour.

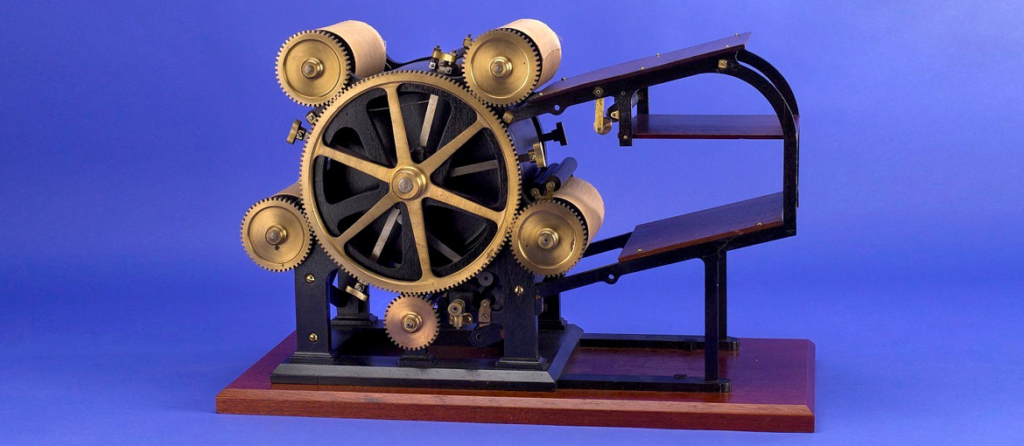

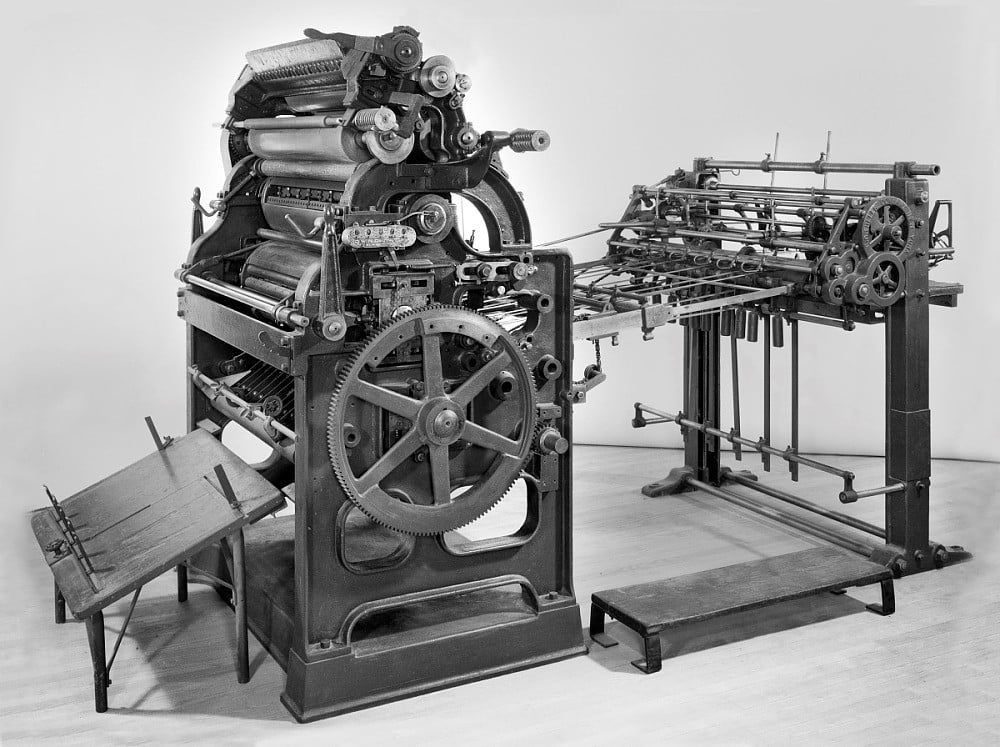

The paper offset printing press

This you see is the first paper offset printing press and it was born out of a mistake. But we’ll get to that in a moment.

The offset printing technique is one of the inventions made possible by the rotary press mechanism. It is in fact based on three cylinders: the image is transferred from the inked form to an intermediate cylinder covered with rubberized fabric (blanket) and from this to the printing medium.

Precisely the transfer of the image to the rubber was born out of — an oversight. In 1901, American lithographer Ira Washington Rubel forgot to insert the sheet into the lithographic press he was using so the image remained imprinted on the rubber of the cylinder that served to hold the paper firmly in place. When, realizing his mistake, he inserted the sheet between the cylinders, Rubel noticed that the print from the rubber cylinder was much better defined than the print from the stone die.

Immediately Rubel realized the importance of what he had discovered. He set up the first offset printing press that exploited this principle in a small factory in New York. The first model was purchased by the Union Lithographic Company of San Francisco in 1905 and was shipped to the West Coast. But a terrible earthquake in San Francisco and a fire at the Port of Oakland delayed the arrival and commissioning of the machine, which did not begin to be used until 1907. It printed about 2,500 sheets per hour.

This same machine is now preserved at the Smithsonian Institute in Washington, DC (which we also discussed here).

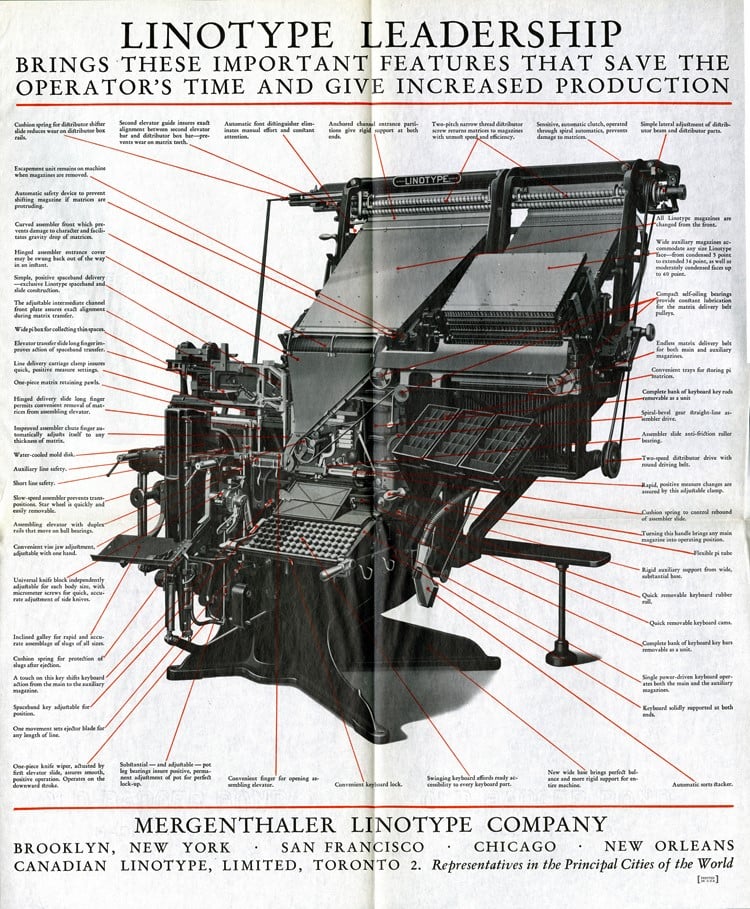

Linotype

From the invention of printing to the industrial age, there was one activity that remained unchanged for four centuries: page typesetting.

In the lively workshops of publishers in the fifteenth century as well as in the great nineteenth-century printing houses, the typesetter continued to work manually arranging character after character to form the lines in the typesetter. The page thus created was ready to be inked and sent to press. After that, the compositor had to break down the page.

With the invention of the steam engine and the beginning of the industrial revolution, an attempt was immediately made to mechanize this operation, but for many years inventions followed one another without particular success. Then came the linotype.

Invented in 1881 by a German emigrant to the United States, Ottmar Mergenthaler, the Linotype (contraction for “line of types”) revolutionized the world of printing, spreading in just a few years.

It was the first automatic typesetting machine: it was a kind of typewriter connected to a miniature foundry. The linotypist typed the text on a keyboard; pressing a key freed the corresponding character matrix that would “fall” onto the line of text. Once the line was completed, it was automatically transported to another area of the machine where molten metal was poured into the dies. An entire line was thus formed. The cast and stacked rows were finally inked and used to imprint characters on the sheets.

In this interesting video we see all these steps operated in a historical machine at the Museum of Printing and Graphic Communication in Lyon, France.

The first linotype was installed in 1886 at the New York Tribune. The machine was extremely complex, composed of thousands and thousands of parts, and the history of its invention is made up of continuous improvements carried out with a lively entrepreneurial spirit (you can find an interesting insight by an enthusiast here).

In 1889 the linotype earned the “Grand Prix” at the 1889 Paris World’s Fair, and within a few years it spread widely to printers halfway around the world. Only with the advent of photocomposition in the 1970s did this remarkable machine begin to fall into disuse.

The Lumitype and photocomposition

In the mid-twentieth century, the Linotype’s “hot” typesetting process began to be replaced with “cold” typesetting. It is another revolution: photocomposition is born. No more lines of characters cast at the moment, page composition is done on a machine and through a photounit imprinted on film.

From the film, plates could more easily be impressed for use in offset printing.

The first photocomposition machine was called Lumitype and was invented in 1946 by two French electrical engineers, René Higonnet and Louis Moyroud. However, the two had to move to the United States to find someone interested in their invention.The Lumitype Photon was born, produced by Lithomat in New York in 1949.

The first book entirely typeset with photocomposition was titled “The Wonderful World of Insects,” and the back cover had these words, “We are proud that the book was chosen to be the first work composed with this revolutionary machine . . .”

Photocomposition in the 1970s became cheaper and freed up the creative energies of even small printing companies: it was possible to use an unimaginable amount of fonts before, they could be printed in any size, and they were much easier to compose along with images and graphics.

The computer

Bringing about the decline of the photocomposer was another, extraordinary machine: the computer.

Beginning in the 1980s, the spread of computer tools made it possible to compose the page on the video screen. The latter could be with the Computer to film technique, which allows the film to be obtained and then used for the creation of the printing forms; or with the Computer to plate technique, which allows the printing forms to be obtained directly, eliminating all the steps of photocomposition (mounting, film exposure and development, and plate exposure and development).

Personal computers begin to appear in every home, making it possible for anyone to layout their own documents and, with the invention of inkjet and laser printers, print in their own homes. It is the beginning of the digital revolution-but that is a whole other story.

What will be the next machine to radically change the world of printing?