“Pictogram” is a word that is not new to you, is it?

This refers to a specific universe of signs developed in modern times, but with very ancient origins. Basically, it is a drawing conventionally taken as a sign of something. A recently accepted and more detailed definition, based on semiotics, sees a pictogram as an illustrated representation; an iconic sign that represents complex facts, not through words or sounds, but by using visual containers of meaning.

These have provoked the thoughts of leading designers and scholars from around the world. Definitions developed over time approach pictograms from one point of view, looking at history, function or visual rendering, but as reported above, these are instead multifaceted. Indeed, they present different elements in terms of relationships: between the sign and what it means, the formal technique, the meaning, and the goal it is supposed to achieve. In short, pictograms seem like a simple matter, but they open a window to an interesting and not at all trivial world!

According to Otto Neurath (economist, philosopher and inventor of the Isotype system) a pictogram is an element of a system with absolute validity. Otl Aicher (graphic designer and founder of the Ulm School) stated that “the pictogram must have the character of a sign, but without being an illustration.” For Herbert W. Kapitzki (former professor at the University of the Arts in Berlin and co-founder of the Institute for Visual Communication and Design) “a pictogram is an iconic sign that depicts the character of what it is intended to represent, and uses abstraction for its sign quality.”

History of pictorial signs and some relevant examples of pictograms over the millennia

Where did pictographs originate? Do they have ancestors? And how have they evolved over time? Here’s a little journey through the millennia and centuries to bring you pictorial signs in their different declinations, right up to the modern pictograms in use. If we were, in fact, to find an ascendant to pictograms, they would be the so-called pictorial signs, which are nothing but graphic expressions applied to two-dimensional media.

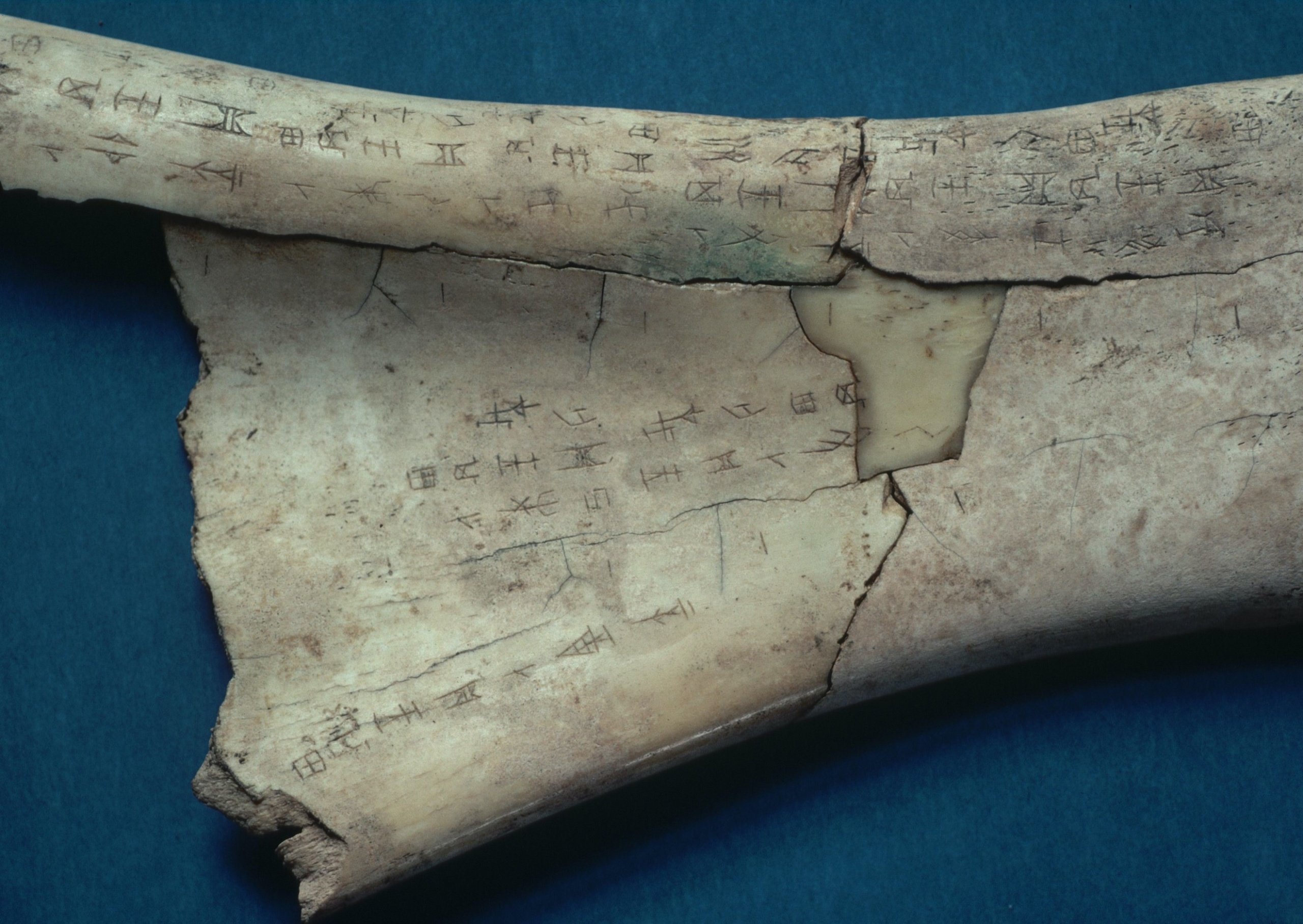

The only language that still exists today that derives directly from pictorial signs is Chinese. In fact, the earliest Chinese inscriptions date back to 1200 B.C., and they are the famous oracular bones, containing precursor symbols of characters still in use.

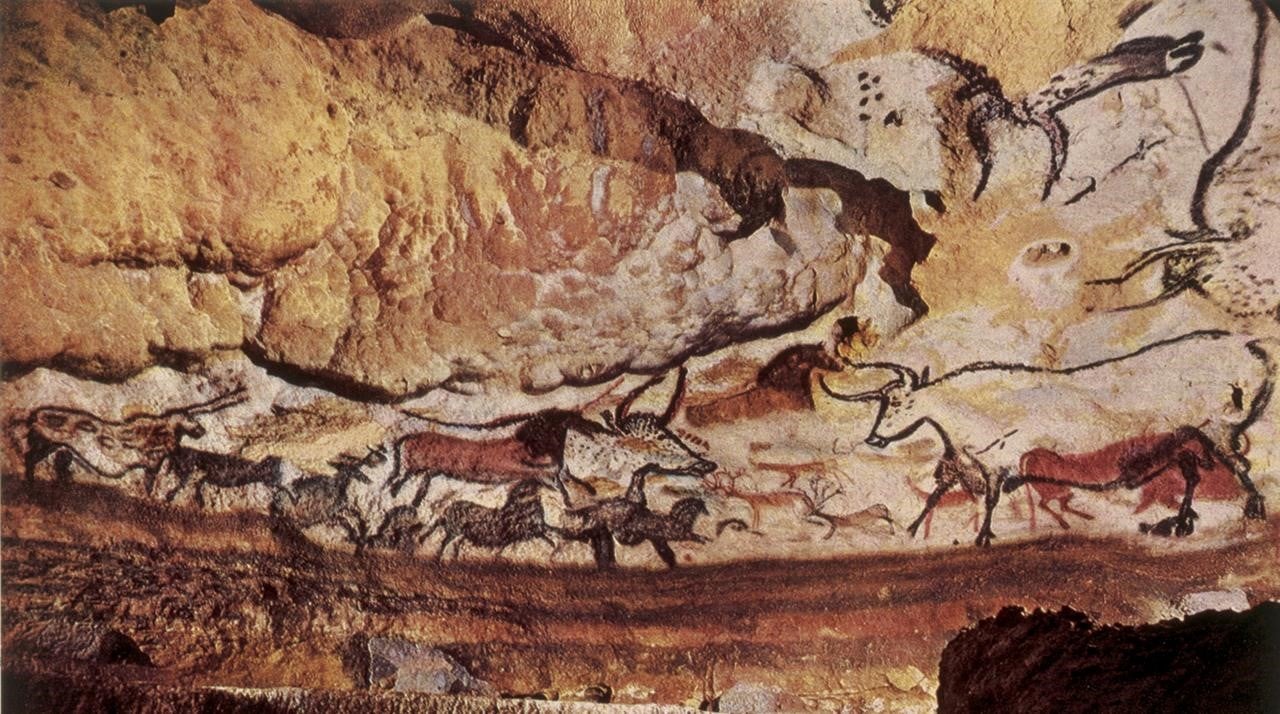

Pictorial signs have changed considerably throughout history. The oldest date back to about 30 000 B.C., in the form of wall paintings within a cave complex near Montignac, France (the Lascaux Caves). It remains unclear why these 6,000 figures (including animals, human figures and abstract signs) were painted, but it is certain that they were not used to communicate a specific message.

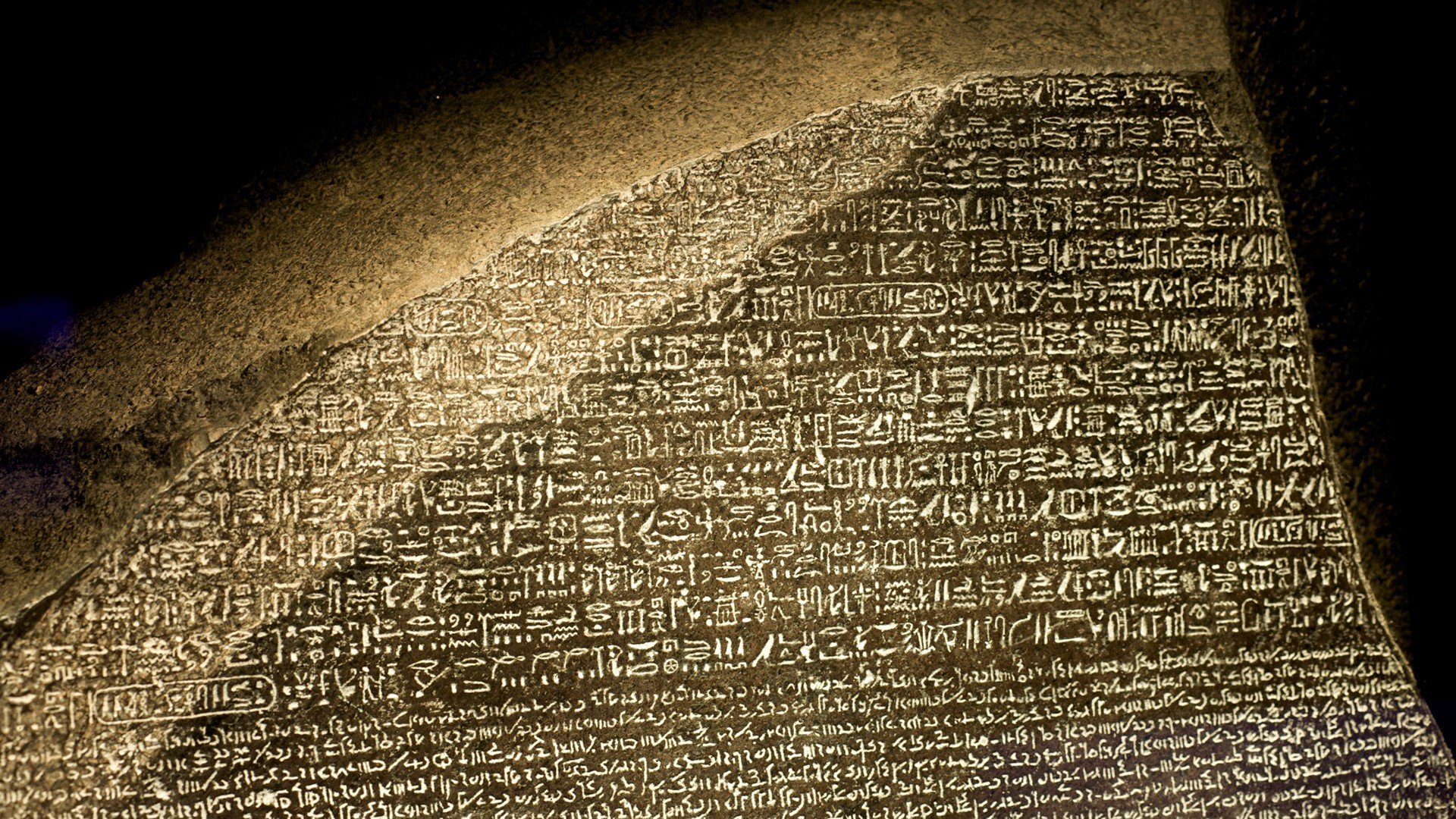

Another important example of these signs are Egyptian hieroglyphs, Mesopotamian cuneiform writing, and Mayan glyphs, all from the same period. In this case they were actual languages that exploited a pictorial sign system. Thanks to the discovery of the Rosetta Stone in 1799 (which bears the same inscription in Egyptian, Demotic, and ancient Greek hieroglyphs) it was possible to decipher hieroglyphs for the first time, and to understand that they represented precisely sounds of a language that once existed.

In the 12th century, a new type of pictorial markings emerged that survives to this day among the noblest families: the heraldic coat of arms (or blazon). This was applied to the helmet and armor of knights during the Middle Ages, and later became the family coat of arms.

With the invention of printing in the 15th century new signs appeared, ornamental friezes inserted into the pages of books called vignettes. Originally with floral motifs (in fact, the name comes from vineyard), these later expanded on various themes, including religion, holidays, the months, the seasons, and animals.

The pioneers of pictographs

From a certain point in modern history, pictographs became prominent.

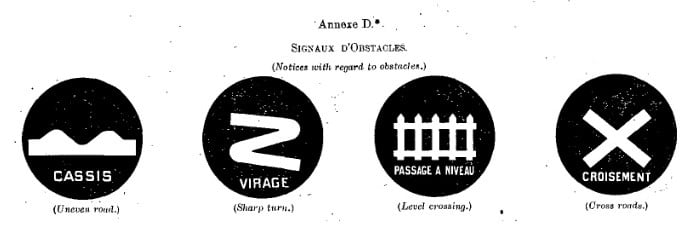

The rise in popularity of the automobile and the construction of an increasingly dense network of roads led, in 1909 in Paris to the proposal of an international system of 4 pictograms for road signs, accepted by Austria, Belgium, Bulgaria, France, Germany, Italy, Monaco, Spain, and the United Kingdom. In 1927 the system was extended and recognized by the Traffic Committee of the League of Nations.