When we talk about the “history of printing,” we refer to the history of printed words. However, in parallel to the printing of words, the printing of another system of notation develops: that of music. Text and printed scores develop in parallel, sharing technologies and advances, but the publication of music in printed format brings with it complexities and challenges that have sometimes diverged its evolutionary path.

Below you will find highlights of this journey, in which musical notation has been invented and re-invented several times, developing from some simple directions on how to enunciate the verses of a song, to a complex system capable of giving precise information on notes, pitch, rhythm… for an entire orchestra.

Antiquity: the ancestors of modern sheet music

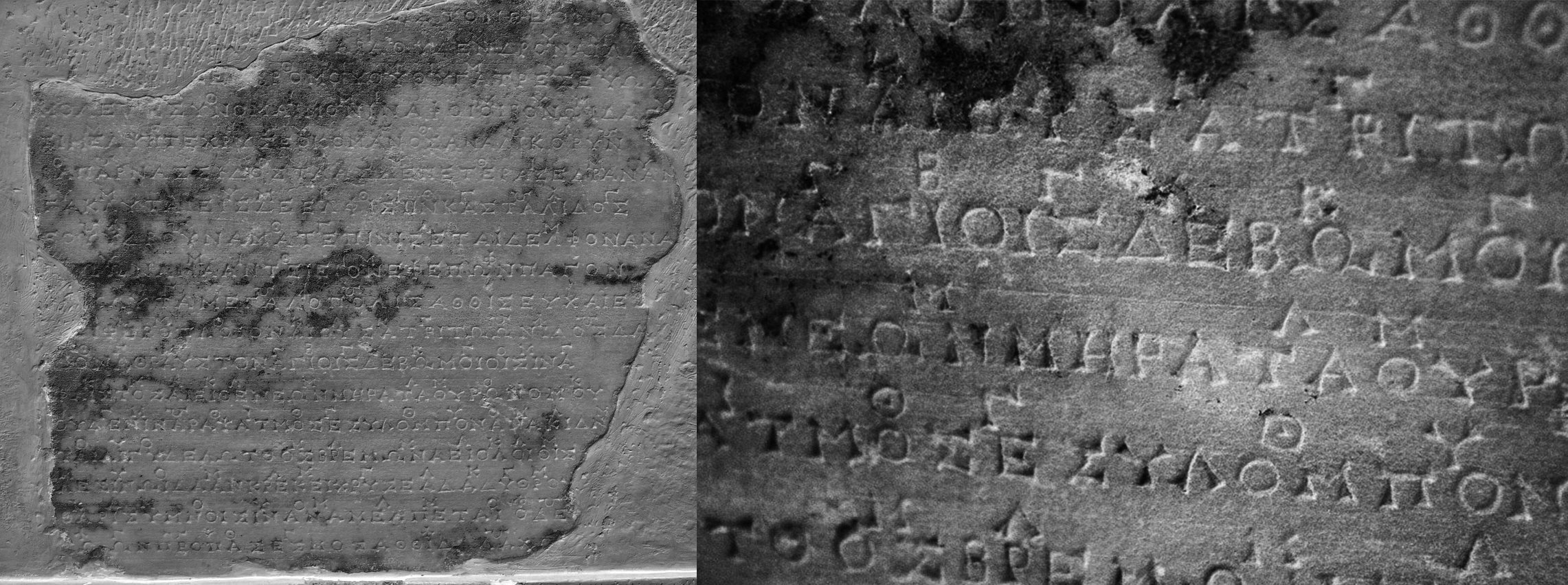

The earliest forms of musical notation are found even before paper and parchment were used as writing media. The earliest form ever was found in a cuneiform tablet created in Babylonia (modern-day Iraq), circa 2000 BCE. Forms of musical notation were also common in Ancient Greece from at least the 6th century B.C., in which symbols placed over syllables gave pitch information.

Temple of Apollo

a

Delphi

, on one of the outer walls of the Athenian Treasury. They date the first to 138 BC and the second to 128 BC.

Middle Ages: music in illuminated manuscripts

The conception of modern musical notation, with the systematic adoption of the tetragrammaton (later replaced by the pentagram), is due to Guido monk around the year 1000. Although in most cases music continued to be handed down mainly orally, within the abbeys music began to be transcribed by hand with great laboriousness in illuminated codices, accompanied

by precious illustrations and decorations.

Codex Squarcialupi, manuscript music codex made in Florence in the early 15th century, Biblioteca Medicea Laurenziana (Florence).

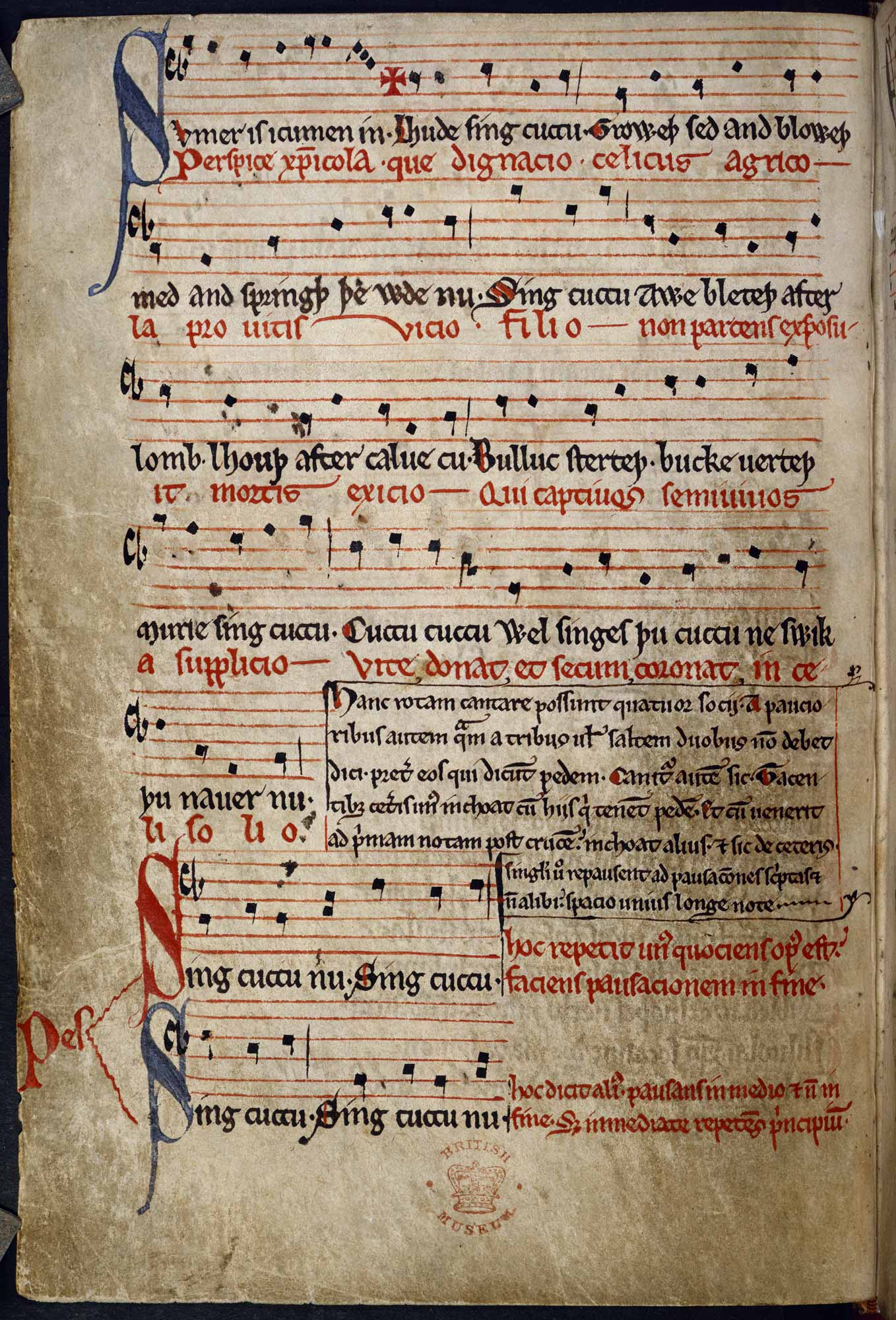

‘Sumer is icumen in’, late 13th-century medieval English canon, British Library.

Movable type printing: Ottaviano Petrucci and John Rastell

With the invention of movable type printing in the 15th century, printing famously became the most common means of producing and disseminating texts, while instead music continued to circulate on handwritten codices. This was due in part to the lack of a uniform and shared musical notation, but mostly to the technical difficulty of integrating and aligning musical notes and lines, as well as any text. Often, the lines were added by hand before or after the music was printed. Other times, however, the lines were printed, and scribes would then add notes and lyrics by hand.

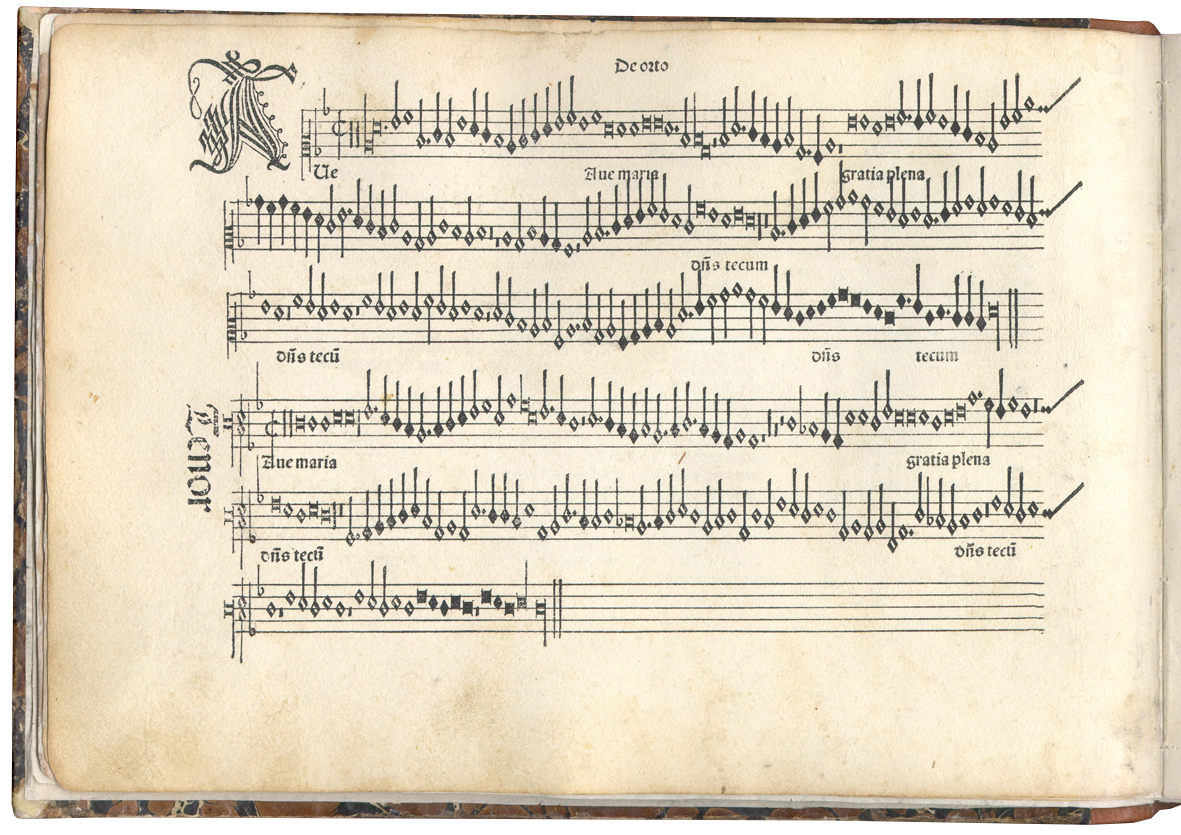

Ottaviano Petrucci, one of the most innovative printers of music at the turn of the 15th and 16th centuries, adopted a system that involved triple printing of lines, text, and notes in three successive passes. The results were clean and elegant, but the process was too time-consuming and difficult–aligning the three prints precisely in fact required great skill–and was not reproducible on a large scale. In 1520 the Englishman John Rastell devised a different model in which lines, words and notes were all part of the same typeface and therefore only one print was needed. The method was preferred to Petrucci’s, although with less accurate results, and spread throughout Europe, where it became the standard until the adoption of copperplate engraving in the 17th century.

Ottaviano Petrucci, Harmonice Musices Odhecaton, 1501.

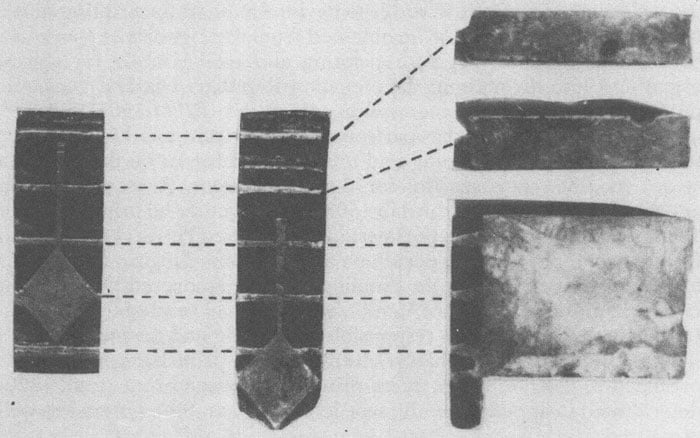

Left: assemblage of characters. Pieces of other characters were added to place notes in different parts of the lines.

musicprintinghistory.org

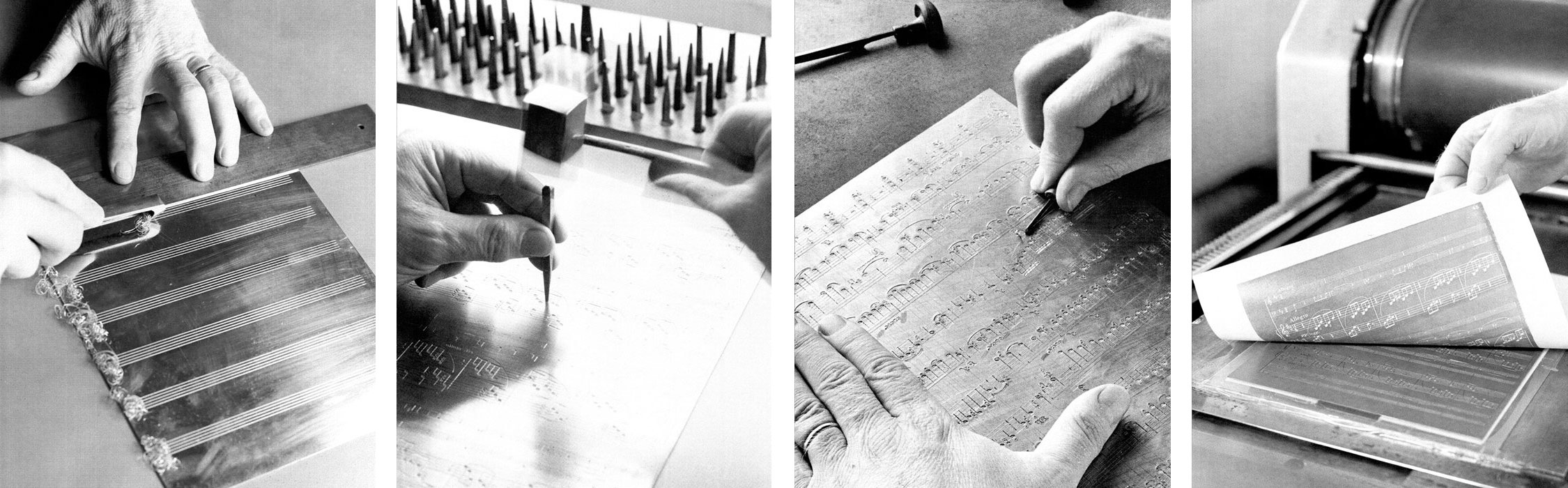

Plate engraving: the most widely used method until modern times

The limitation of movable typefaces lay in their static nature, which prevented them from duplicating many of the details of handmade manuscripts. Printers therefore turned to other printing techniques, including precisely engraving. The process involved engraving lines, notes, and text directly onto the plate, which was then inked and used to print on paper. The printing result is of the highest standard, so much so that music publishing houses such as G. Henle Verlag continued to engrave sheet music by hand until 2000.

At first, the plates were engraved freely by hand. Later, special tools were devised for different elements.

- Chisels for sheet music

- Elliptical burins for crescendo and diminuendo

- Flat burins for slurs additional cuts

- Punches for notes, keys, alterations and letters

Plate engraving was the method of choice for sheet music printing until the late 19th century, when its decline was decreed by the development of photographic technology.

musicprintinghistory.org

Handwriting: the importance of hand notations

The development of sheet music printing contributed to the standardization of musical notation symbols, leaving little room for the inevitable variations that result from hand transcription. Composers nevertheless continued to write their music by hand, before passing it on to a copyist and then to a printer for distribution.

With the spread of engraving printing, sheet music sheets with the lines already printed, on which to write notes, became common. In the 20th century, score sheets were sometimes printed on tracing or veil paper, which made it easier for the composer to correct and revise the work, and also made it possible to reproduce the writing in multiple copies through a photographic exposure process. If the paper used was matte instead, it had to have a fine texture so that the ink would not expand. The ink was always strictly black.

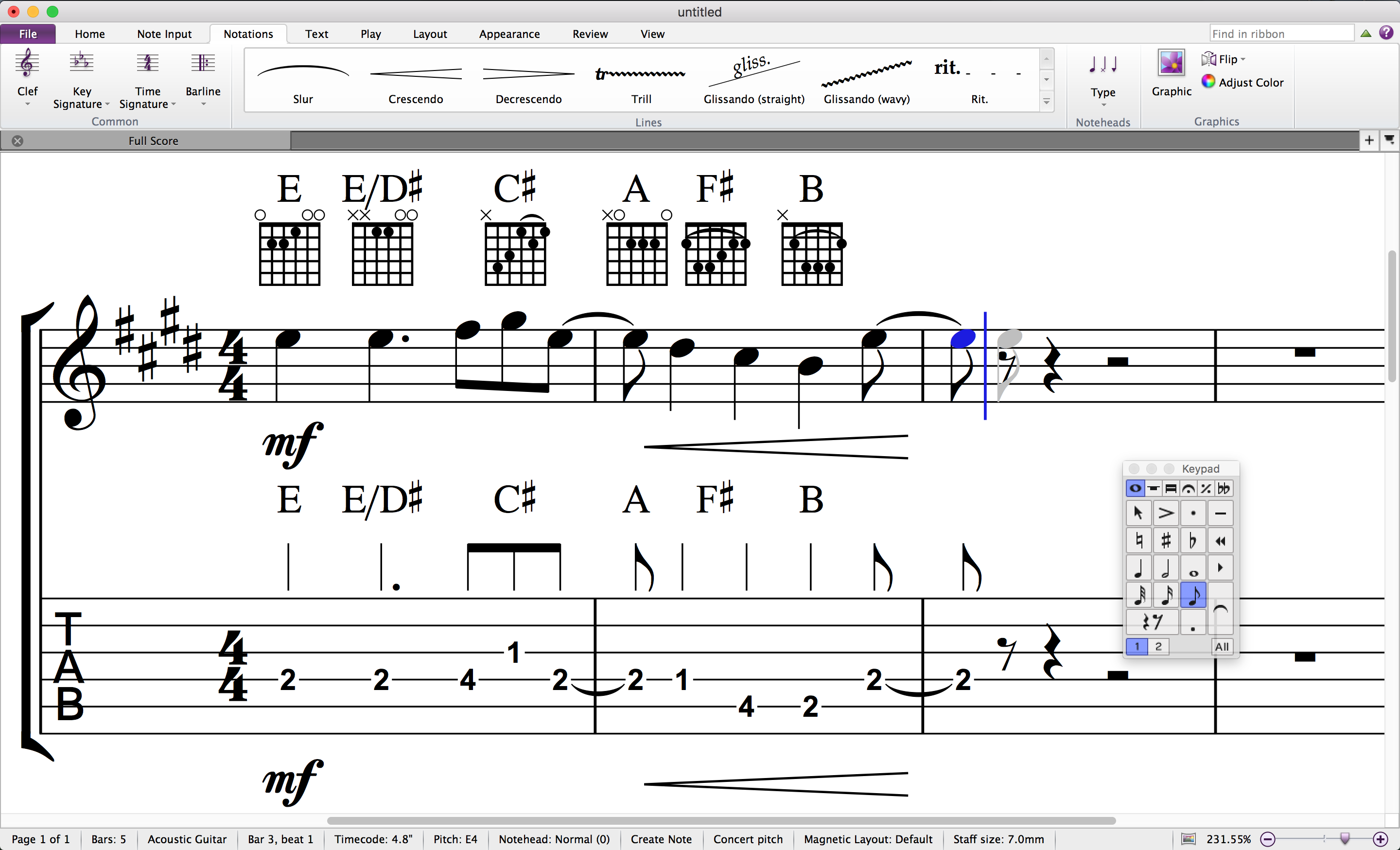

Computers and sheet music: sowftware for music notation.

Like virtually every other process, computers have also revolutionized the way sheet music is written and produced. Indeed, there are now music notation software (such as Finale or Sibelius) that, in a manner not unlike a word-processing program, allows for the typing, editing, and printing of sheet music. Music notation software facilitates various aspects, including making corrections, extracting parts for the orchestra, transposing music between different instruments, changing the key of a piece, and many other tasks. Some software even allows you to test music by digitally playing instruments that give you an idea of what a real instrument will sound like.

Sibelius.

Different methods of representing music continue to evolve. Some as alternatives, or as supporting methods, for particular instruments. For example, there are pictograms for wind instruments, indicating the holes to be covered, or different systems for percussion instruments, which do not produce notes of a specific pitch. Alternative forms of notation also exist for the guitar, a very common instrument today.

In any case, the standardization of music notation in the score form represents a great achievement in Western music education. Printing has been chasing and trying to mechanically reproduce notation as accurately as possible for centuries, but, on the other hand, it is also through printing itself that the standardization of such a complex system has been possible.