Manga is the Japanese term for comic books.It was some artists in the late 19th century who coined this word, among whom was the great Japanese painter and engraver Hokusai, to denote collections of light and pleasing drawings and illustrations.

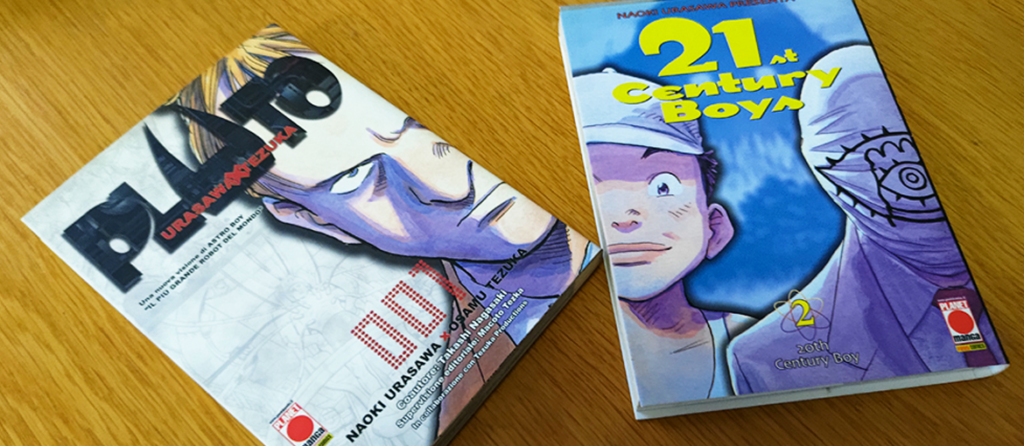

The great success of manga, however, began after the end of World War II. In fact, U.S. troops introduced Disney comic books such as Mickey Mouse and Donald Duck to Japan: this is also where the modern manga of master Osamu Tezuka, the “God of manga,” author of the well-known Astroboy who also signed so many other iconic stories, was inspired.

Today, manga has become one of the main sectors of the Japanese publishing industry and has long since conquered international markets as well, including Europe.

A great many illustrators and aspiring cartoonists already turn to Pixartprinting to print their stories or create an eye-catching portfolio using the manga technique.

Many people think that manga is actually a graphic and drawing style, but that is not really the case; instead, it is a body of precise techniques.

The oriental vision of comics

As we reiterated in the article devoted to bande dessinée, comics are not the same the world over: depending on geographic area and culture, modes of storytelling, drawing styles, formats, album size, and pagination change.

While American comics generally favor action, color stories, and a more vertical format, and in France stories are published in hardback and with larger plates, manga, on the other hand, is characterized primarily by certain foundational elements regarding storytelling and formats:

- The emotion of the characters in the service of the story

- Smaller, pocket-sized print formats (called tankobons).

Here, then, is a guide on how to make comics using the manga technique-a topic that is certainly vast and for many authors requires years of study. This guide therefore does not pretend to be exhaustive, but is an introduction for those who would like to make their passion a job, or for those interested in better understanding the codes and the oriental vision of comics.

Salvatore Pascarella: our guide to learning about manga

So how to make a manga, whether you want to create a portfolio to show to publishers or a self-produced comic book?

Before starting with the actual drawing, it is good to understand that at the basis of any comics technique there are deep structures and visual codes that are reflected in the culture of the country of origin. We are obviously not talking about indissoluble rules, but guidelines that have developed naturally over time, thanks in part to certain authors, who have influenced the structure of the page and the timing of the story.

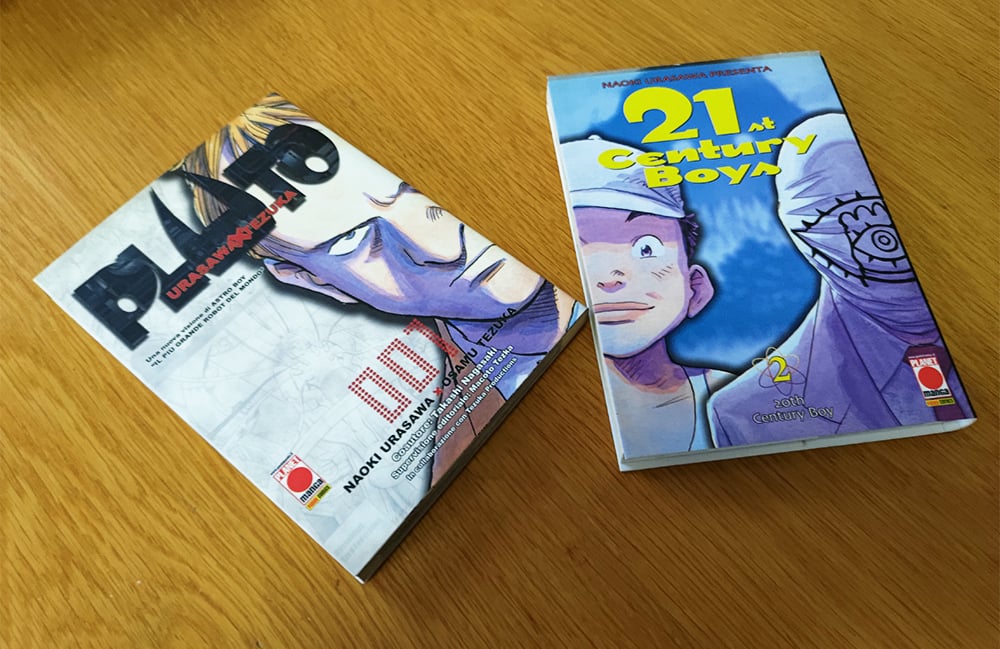

To understand the vast world of manga, we spoke with Salvatore Pascarella, aka Salvatore Nives, Italian mangaka and author of the two-volume manga series Flare-Zero (for publisher EditionsH2T in France and in Italy carried by Shockdom) and the four-volume sequel Flare-Levium.

The grammar and fundamentals of manga.

The basis of the elements that make up a comic strip is the same all over the world:

- The vignette is the single image drawn

- The cage is the set of vignettes that make up a page or board

- The closure is the “white space” that defines the time of the story.

Manga has now become internationalized: it is not relegated only to Japan, which exports its stories and authors, so there are more and more publishers and authors even in Europe who have inherited this comics technique.

According to Salvatore Pascarella, the basic matrix of Oriental storytelling, called Kishōtenketsu, is the rhythmic score that all manga authors use to create both the double pages (everything the reader sees by opening the album) and the stories:

“Mangaka always follow 4 times: beginning, development, turning point (climax), and end, unlike Western storytelling, which follows a 3-step score, i.e., beginning, development, and end. However, the Japanese also apply this 4-step score to individual pages. Tezuka did just that in the early days with his work ‘Treasure Island’: he took these 4 tenses typical of yonkoma (vertical strips of 4 vignettes) and combined them with his studies of Disney cinematography, trying to innovate the medium from the point of view of direction and timing.”

The authors who have influenced and built manga over time are many, impossible to name them all. Among them are certainly:

- Osamu Tezuka: the true pioneer of modern manga, who literally invented the “big eyes,” which later became hallmarks of many (but not all) anime. He is regarded as the father of “story manga,” referring precisely to the 4-part narrative structure mentioned above.

- Shōtarō Ishinomori: created among other things some of the most popular Japanese manga series such as Cyborg 009, which were extremely influential for all subsequent authors.

- Katsuhiro Ōtomo: created Akira, a series with a very strong cinematic impact, which allowed manga and anime to go outside Japan.

- The Group of ’24: a group of female comics creators who heavily influenced the so-called shōjo manga (girls’ comics), starting in the years ‘ Before that time, girls’ publications were by men only.

- Akira Toriyama: allowed manga to become mainstream with the well-known Dragonball and Dr. Slump series.

This might be a good starting point for understanding the deeper structures of the manga. The important thing is not to stop at just the “masters,” but to take a look at current publications as well.

The defining elements of manga

To create a manga page, one needs to know some of its most characteristic elements.

According to Salvatore Pascarella:

“one of the basic guidelines for creating a page is to always follow the emotions that you want to communicate to the reader at that moment. So you can draw a wide and airy vignette if you want to communicate a relaxed mood of the characters and therefore graphic balance between elements of the scene and baloon. Alternatively, the author creates imbalance in the scene: if you want to communicate a sense of tension, fear or asphyxiation, you tend to slant the vignettes, compress them, create tangencies between elements. Building on these premises, you can create different page layouts.”

Manga certainly has so many other characterizing elements that distinguish it from Western comics. In addition to Kishōtenketsu, which is the basis of the narrative, Pascarella pointed out a few, the most obvious ones:

- Right-to-left reading: unlike Western comics, manga is read “backwards.” Some Italian authors, however, do not follow this oriental layout.

- Stop/Control time: in manga (for which the rule 1 vignette = 1 emotion applies) time can be much more dilated to allow the reader to synchronize with the reading time and thus “experience” the story firsthand. The size of the vignette is closely related to the reader’s emotion. The larger this is, the more time slows down, creating more emotional tension

- Hikigoma: this is the last vignette present at the end of the double page, that is, what the reader sees before turning the page. Here the authors usually insert cues of interest, something special that entices the reader to turn the page, a kind of mini-climax.

In short, in manga to govern the layout of the page and its structure are the emotions one wants to communicate, as well as a narrative structure that always keeps the reader’s interest high.

The manga board and the finished product

For manga over time a decidedly “free” cage has been codified: the author can superimpose vignettes, enlarge or shrink them at will, and more. In general, an album is characterized in this way:

- Each page usually consists of 3 strips, but in some cases it can be as many as 4.

- Each panel has from 1 to 8 vignettes, and this obviously varies depending on what you want to communicate. More rarely there are more than 8 vignettes and on average you see 4 to 8 vignettes per page.

- Each volume ranges from 180 to 200 pages

Clearly these are general rules and each publisher (both in Japan and European publishers who publish manga) follows its own cage and number of pages. For example, some Italian authors use the 100-130 page format: a lot depends in fact on the story and what you want to tell.

But how do you structure the drawing sheet of a manga? Again, there is no universal standard, but in general “there is the cage that delimits the closed vignettes and texts, then there is the outer margin for the drawings/live vignettes,” says Pascarella.

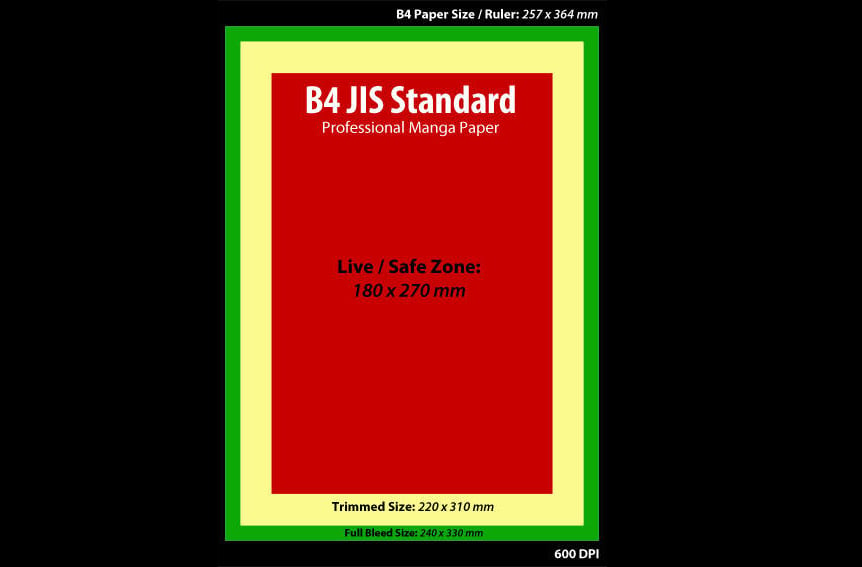

As for the format, many use the B4 format (others a more common A4). Here’s how to read the image below:

- The red area corresponds to the edge of the vignettes and cage

- The yellow area is the margin at the edge of the page, so where it will be cut at the green area.

- The green area is the outer cage, which is then removed at the printing stage.

In the yellow area it is then possible to draw, but it is best not to include elements that are essential to reading (such as dialogue), because they may blur too far into the center of the book.

The finished product is usually printed in black and white, traditionally in a print publication format that measures 13 x 18 cm (but there are many other formats, however). At Pixartprinting you can choose from a variety of formats in the books, magazines and catalogs section, including paperback. If, on the other hand, you want to create a portfolio of boards or drawings you would go for a greased and milled, or stapled, paperback binding.

This concludes this introduction inside the boundless world of manga: the advice is always to read as much as possible about the authors and stories of this great tradition, so as to fully understand the narrative structures and techniques and why not, discover new exciting stories.