Since ancient times, humans have sought techniques to be able to quickly reproduce shapes and marks automatically, without having to resort to drawing each one. More than 35,000 years ago humans used their hands as stencils on which to blow pigment, to decorate their cave. This was not a simple drawing, but an automatic gesture that allowed for rapid, albeit rudimentary, “mass” reproduction.

Today, printing on an industrial level appears to be as far from a manual and instinctive gesture as possible; in fact, it is a mechanized process, using the most advanced technologies. Nevertheless, with the exception of digital printing (made possible only thanks to computers), almost all other printing techniques used today are actually the technological evolution of manual processes devised centuries and centuries ago.

The main sign reproduction techniques devised by man over the centuries are described below. Some are now obsolete for large-scale use, but nevertheless still appreciated in the artistic field for their peculiarities. Other techniques, however, have been progressively perfected and mechanized to cope with industrial production, but still retain the basic principle of the technique.

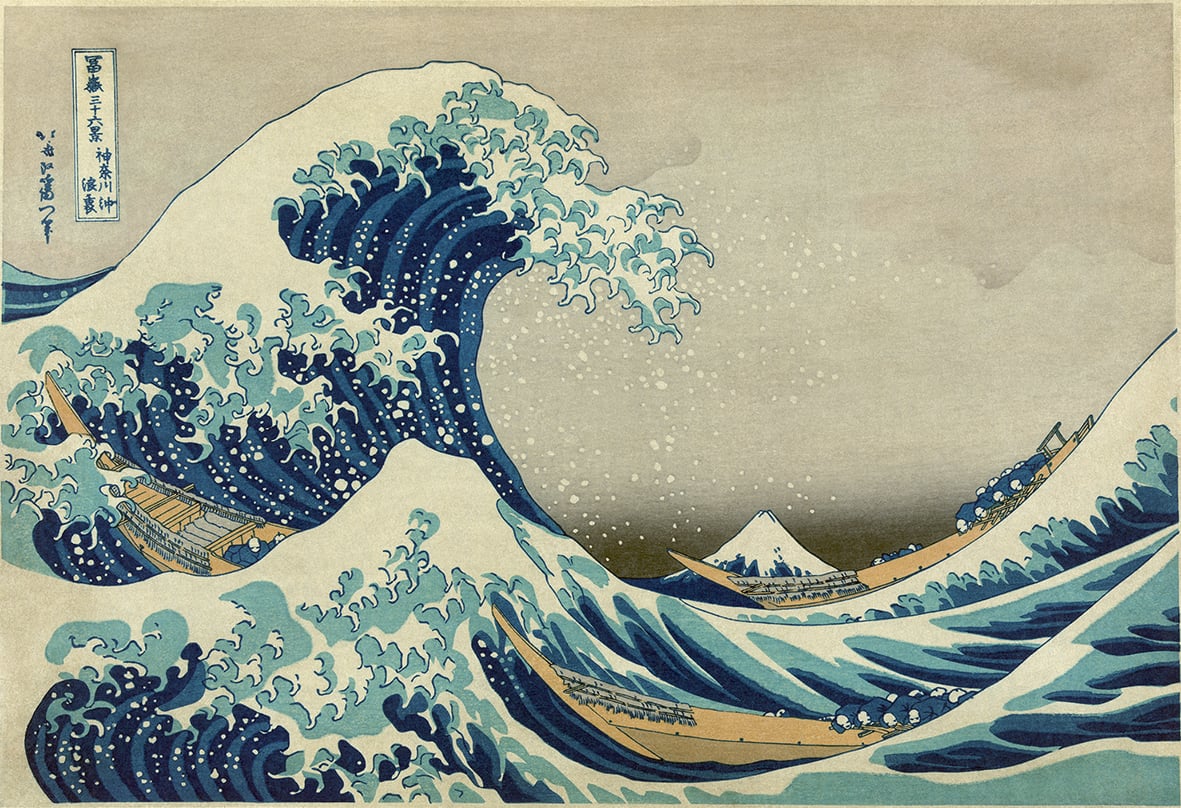

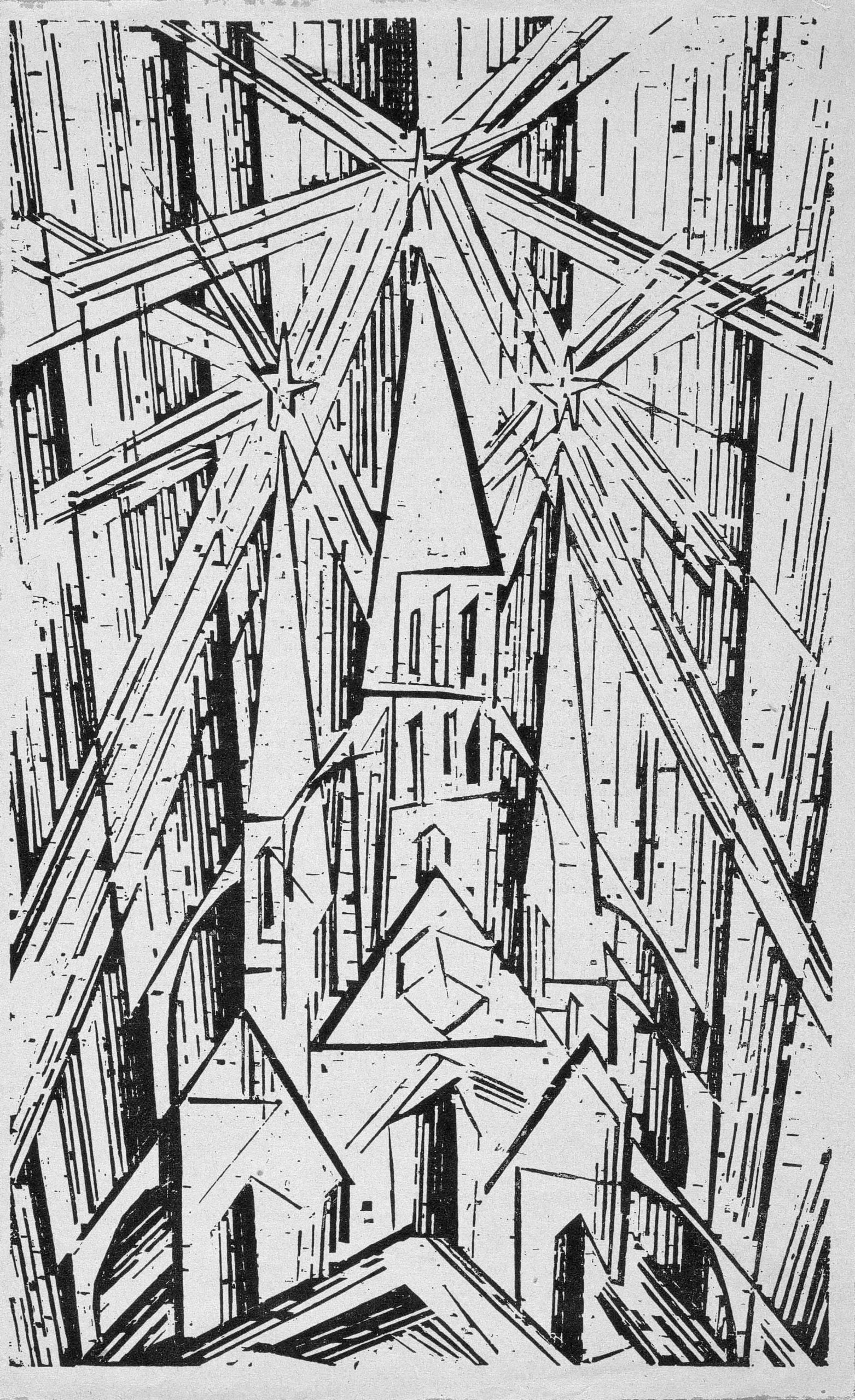

Xylography

From the Greek ξύλον, xìlov, “wood” and γράφειν, gràphein, “writing”

Woodcut is the oldest known method of printing. The technique involves the relief engraving of a wooden tablet using a point, with which the non-printing parts are removed. The relief parts are then inked in such a way that, when pressed onto a support (paper or fabric), they bring back the mirror image to the carved one.

Xylographic printing was also used to print entire books, the matrices of which featured text and illustration paired together, until the introduction of movable type printing, devised by Johannes Gutenberg in the second half of the 15th century.

However, woodcut remained in use in the arts. In more recent times, linoleum and Adigraf, being softer and easier to engrave, have often replaced wood as the basis for engraving. In this case it is referred to as linocut.

Calcography

From the Greek χαλκός, khalkòs, “bronze” and γράφειν, gràphein, “to write”

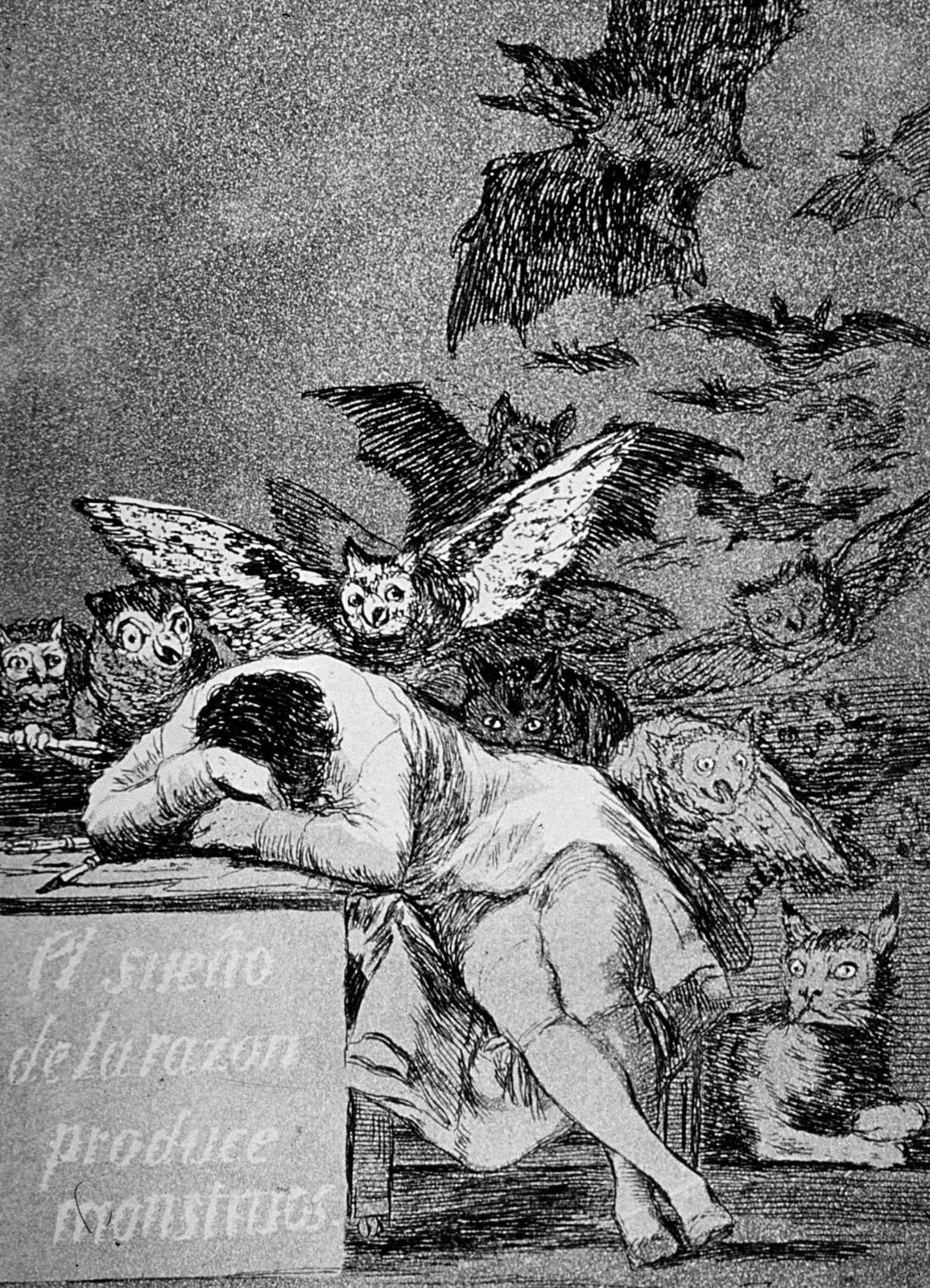

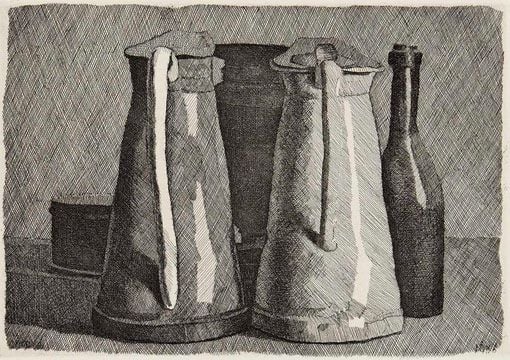

Intaglio is an engraving technique used to represent illustrations. Unlike woodcut, it works in the positive, not the negative: the elements that are later to be printed are engraved directly on the matrix.

The process involves etching a metal plate, and then distributing ink into the recesses, that is, the etched parts. Through the pressure exerted by a press, the ink deposited in the hollowed parts is transferred to the sheet.

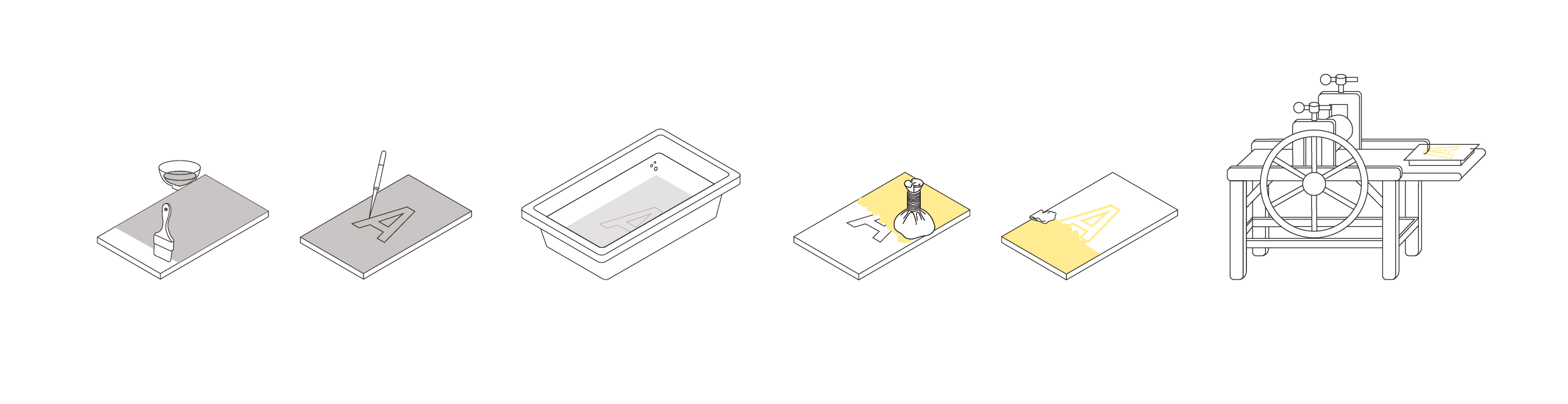

The direct method involves engraving by hand, while the indirect method, called etching, relies on the use of corrosive chemicals to engrave the design previously made on the metal plate. In this case, the plate is prepared with opaque substances capable of resisting the acid; then with the help of a needle the substances are removed at the parts to be printed, which will then be etched by the acid. The depth of the etching is given by the immersion time.

Rotogravure or gravure printing is a technical development of intaglio printing, which uses a rotary machine with engraved cylinders, obtained photo-mechanically. Ink is transferred to the paper through a system of cells of different depths. The deeper the cells, the more ink they can hold and the darker the print.

Because of its brilliance and high fidelity of rendering, since the first half of the 20th century its major use has been in the field of widely circulated periodicals, hence the name “rotogravure” as a synonym for news magazine.

Lithography

From the Greek λίθος, lìthos, “stone” and γράφειν, gràphein, “to write”

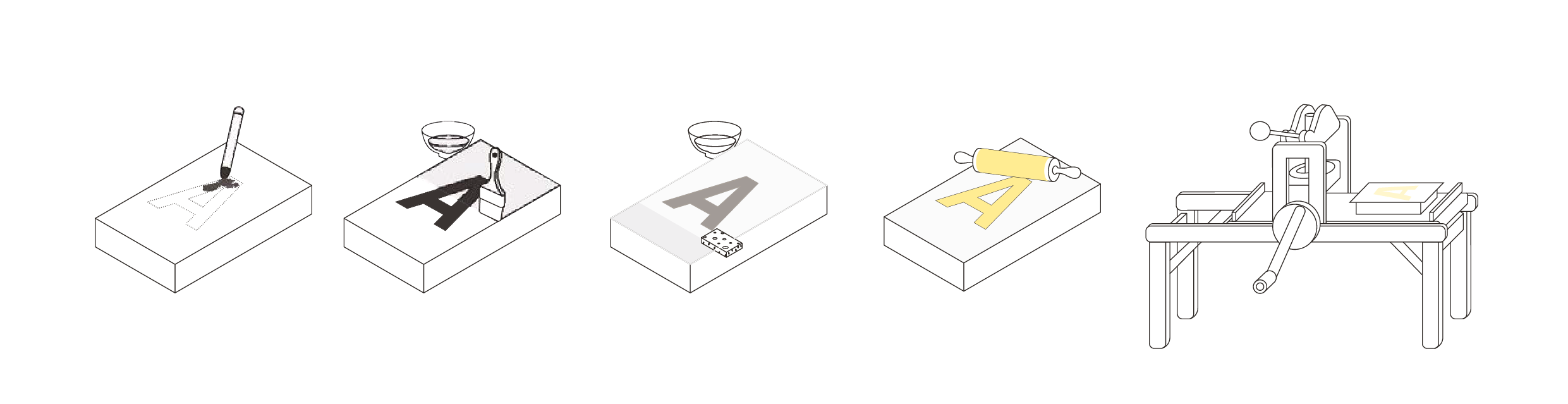

The main feature of lithography, which is based on the different chemical reaction of color and water, is that the printing and white parts are on the same plane. The process involves the use of a special kind of porous limestone, which is drawn with an oily pencil and then immersed in water. While the undrawn parts absorb a film of water, those with the greasy mark repel it; once inked only the previously marked parts retain the ink. By pressing the plate in the press, the ink settles on the paper. For color lithography each color corresponds to a different matrix.

Offset (from English, rebound) printing originates from lithography, which replaces the limestone with a metal plate, on which characters and images are printed by means of film. Printing on paper is done through an interposed cylinder of rubber, which transfers ink by bounce. Photocomposition made it possible to engrave the plate so that it reproduces the image with extreme precision.

To date, offset printing is the most popular system for large print runs.

Screen printing

From Latin seri, “silk,” and Greek γράφειν, gràphein, “to write.”

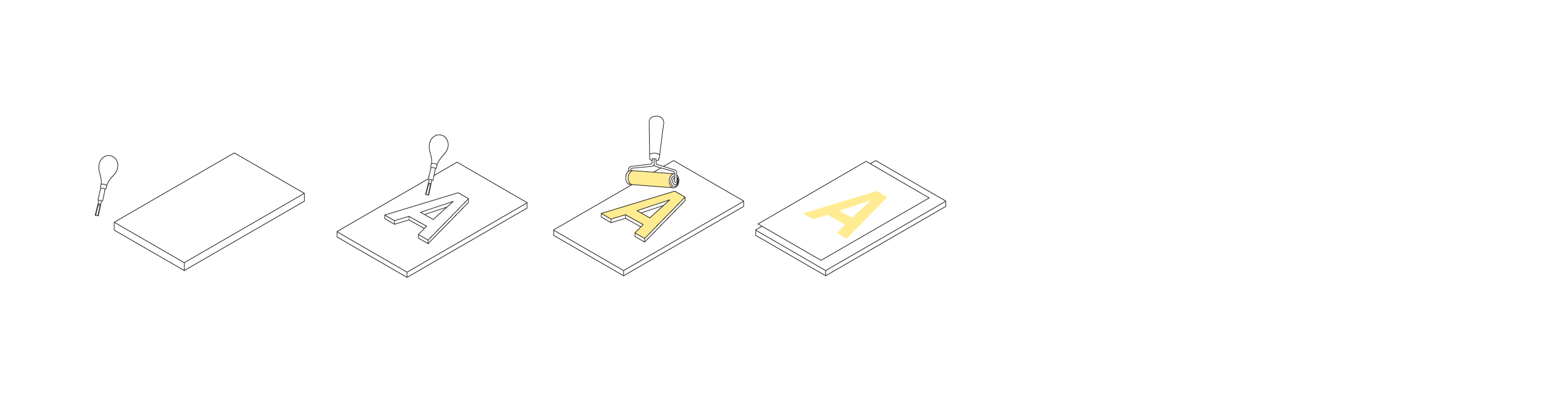

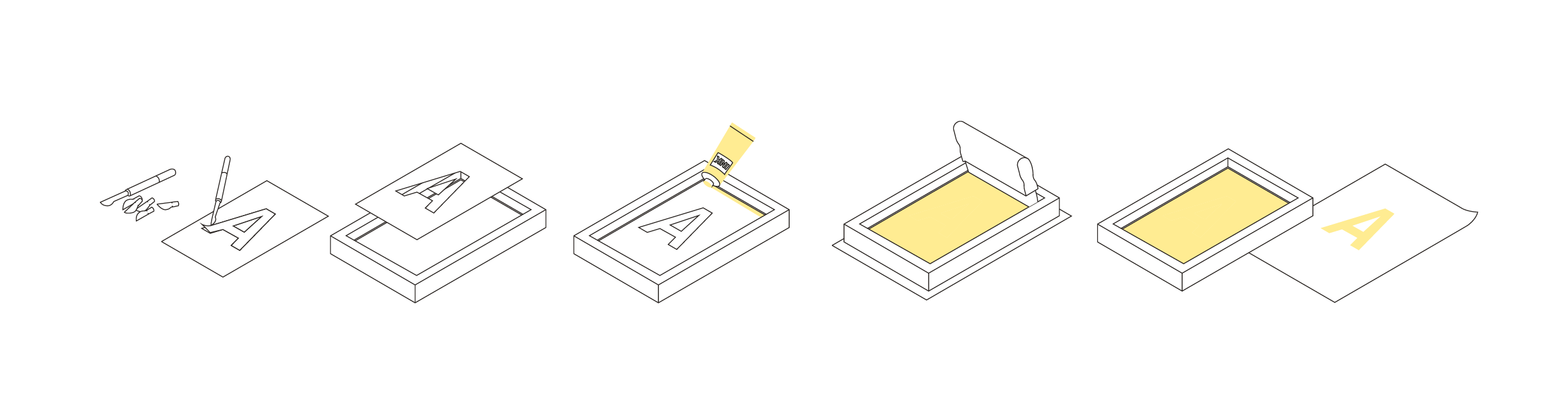

Screen printing is a printing technique that uses a fabric as a matrix through which ink is transferred to the substrate.

Although screen printing was introduced to Europe from the Far East during the Middle Ages, it did not experience widespread use until more recent times.

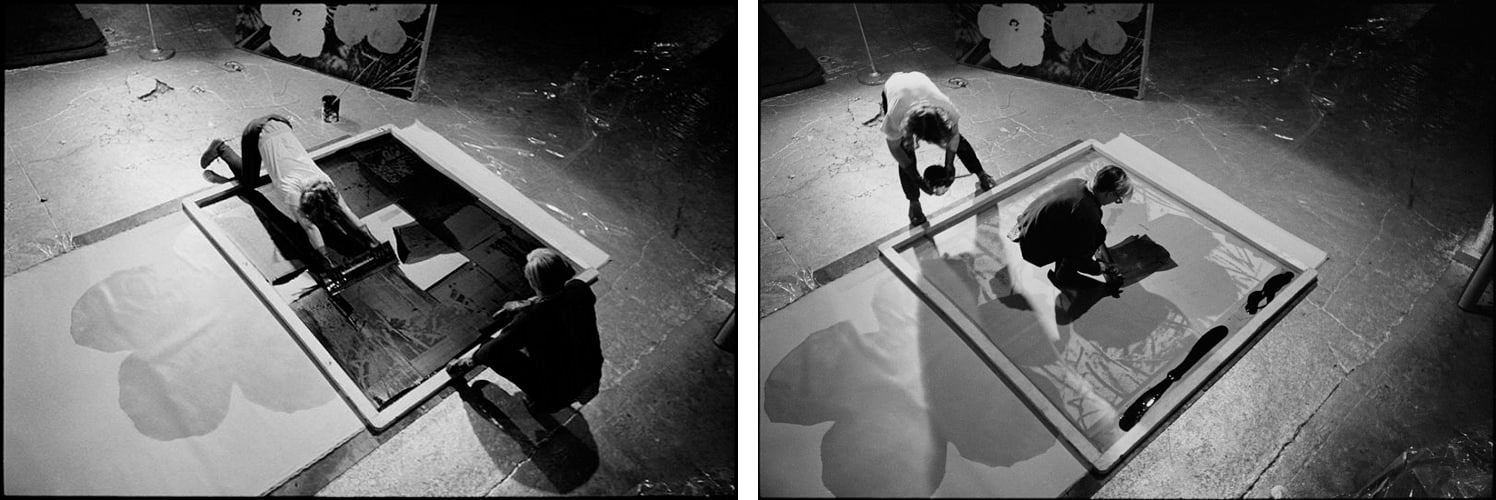

The screen printing stencil, originally made of a silk mesh, now replaced by nylon or other man-made fibers, is waterproofed by emulsion in well-demarcated areas so that the ink can permeate through the unclogged holes in the mesh and pass onto the substrate below the screen printing frame. The passage of ink through the screen printing mesh is accomplished by the gentle pressure of a bar, called a squeezer or squeegee, equipped with a rubber edge that presses against the printing mesh. To produce a multi-color screen print, a stencil must be made for each.

The great advantage of screen printing is the ability to print on a vast number of substrates, dosing the amount of color. This is why today the technique is used both in an artisanal way (in this regard we refer to this article for those who would like to try their hand at it), and in industrial settings, to print street signs, trademarks, license plates, stained glass windows and mirrors, furniture, appliances, sports equipment, shoes, bags…